A Conversation With Sam Prekop, Jeremiah Chiu, and Marta Sofia Honer

Sam Prekop performing with SML at The Empty Bottle, Chicago, 2024. Photo by Charles Bouril.

Sam Prekop’s drawing (Untitled, September 2023), is the cover image on Different Rooms, the new album by Jeremiah Chiu & Marta Sofia Honer.

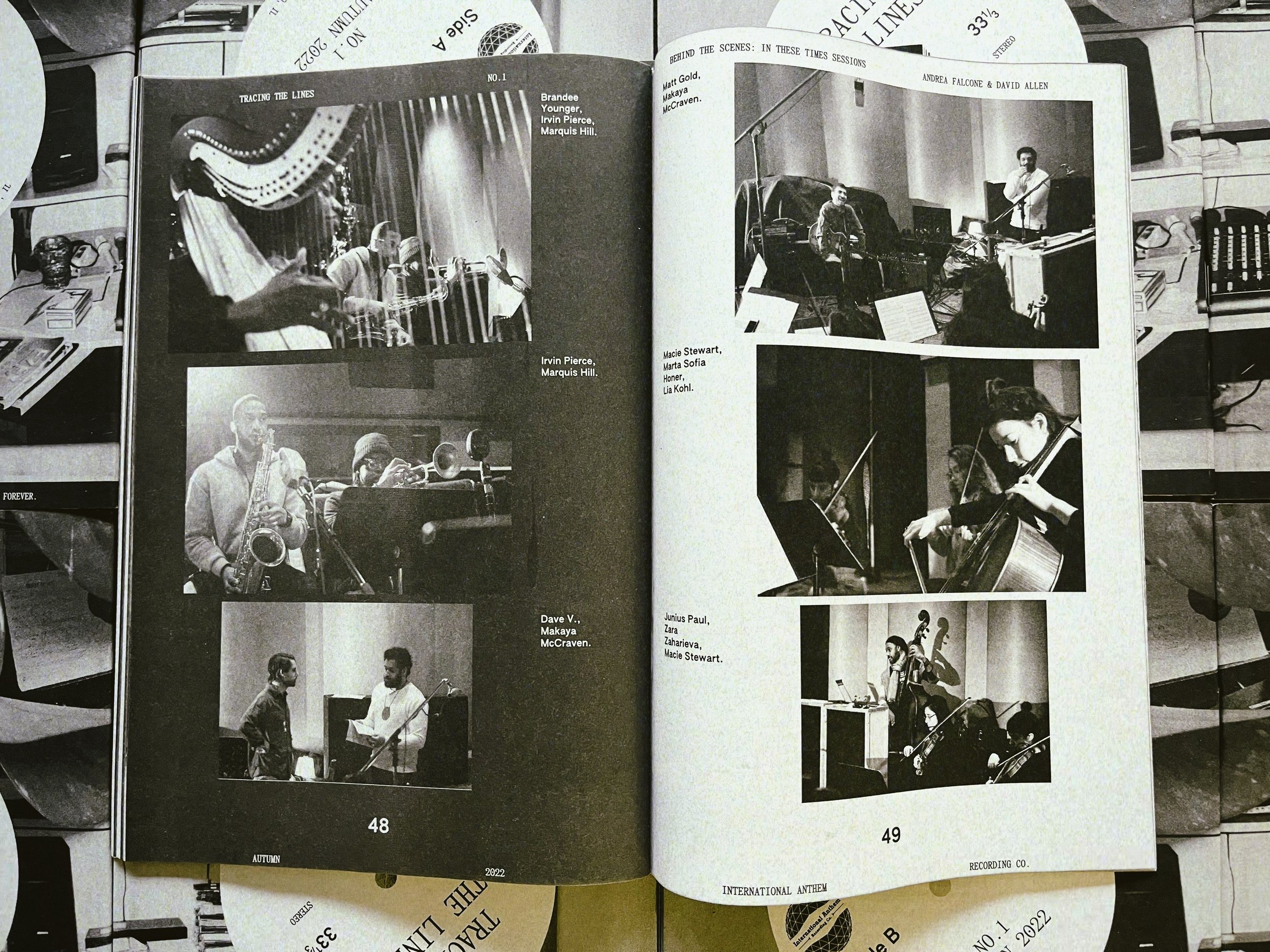

Photos by Charlie Weinmann and Charles Bouril.

Aside from being a Chicago music mainstay and the mind behind long running genre-bending group The Sea and Cake, Prekop has maintained an ever-shifting visual art practice that has casually stretched across the mediums of photography, painting, and drawing for 30+ years.

Tracing The Lines editor David Brown recently spoke with Jeremiah, Marta, and Sam. This is a generously edited rendering of that casual conversation about the evolution of their artistic practices, the niche interests that cemented their friendship, and the process of creating an album package.

****

Jeremiah Chiu:

We met on a Sea and Cake tour. I was playing in the opening band, LA Takedown, and we were just on the Sea and Cake bus. [to Sam] You guys were so nice to have us on there. And then I think after that tour, you and I just kept hitting it off about synthesizers and coffee.

Marta Sofia Honer:

Yeah, after that tour, all of a sudden Jeremiah was texting all the time with the cute little smile that you think maybe someone's texting someone new. A girl perhaps. [laughing]

JC:

Oh, wow.

MSH:

But it was really just him and Sam talking about synthesizers.

David Brown:

If I'm grinning and texting, I'm probably talking to somebody about recording gear or something like that. It's always a safe bet.

JC:

You know, it's quite hard to find people in this particular niche that really understand, where you're like "I like the work you're making with the same tools." And we can also just get overly obsessed with very niche pieces of gear that nobody else wants. [laughing]

DB:

Sam, how did early days of that friendship feel to you? Were you similarly giggle-texting?

Sam Prekop:

Yes. Definitely, I think. What's hilarious to me is we have a very similar collection of gear. It's hardly diverged at this point. So you can see we've been profound influences on each other in terms of buying stuff. Keeping up with the Joneses, you know.

MSH:

Yeah, tit-for-tat.

DB:

Right?

JC:

[to Sam] Well, you have this phrase that you text every now and then that says, "Oh my gosh, this is a must have."

SP:

[laughing] Yeah...must have. Hoping that Jeremiah will buy it and then I can…

DB:

Test it out?

SP:

Live vicariously.

JC:

Since we're both also in the visual world too—specifically with synthesizers—not only does this thing have to sound great, it kinda has to look great too. And it's not the easiest combination of things. I don't think a lot of people really care as much about how the thing looks as much as we do.

DB:

Especially with bespoke gear. It can look pretty raw sometimes.

SP:

Yeah, raw can be good if it's the right kind of raw.

DB:

Always, yeah.

JC:

You have to do some choice making when it comes to all those things. But I thought it was really interesting learning more about Sam's practice, because there's also similar shifting of gears where sometimes he'll just go into the mode of, "I'm just doing photography for a long time." Or "I'm just doing a drawing for a while." [to Sam] Can you talk a little bit about how that sort of cadence works in your life?

SP:

Yeah, I did just switch up to doing more photo stuff, but I don't feel great about it yet because I have synth homework that's due, you know. So perhaps I'm just avoiding it at this point. But I do find it hard to do several disciplines at the same time. The drawing stuff actually occurs in really short spurts. Like a week at a time. In some ways it's my most easygoing creative outlet, and it sort of takes up the slack for not painting anymore. I was trained as a painter. I went to art school. The music thing is all a fluke, and through the music I got into photo stuff. But I don't really have a painting studio right now, so the drawing sort of takes care of that. And to my surprise, it works. It's as good as painting. The same part of the brain is used, and it sort of takes care of those ideas that I need to fulfill. But the drawing is more related to the music. You could equate it to improvising, in a way, because it's really fast. That's an important aspect of it. Each drawing takes maybe 10 minutes or less, and if it doesn't work out, I just do another one. So it's very quick response, in the way that you would play with somebody else musically. So I like to equate the drawings with the music. I think it's more related to the music than my photography in a weird kind of way.

MSH:

Well, it kind of worked itself out then that way, because we love both your drawings and photographs. We have some of your photographs hanging in the studio, and we had initially looked at maybe using one of your photos for the cover before we moved on and kind of settled on the drawing. So it worked itself out.

SP:

Yeah, I thought that was a good move as well. I agreed that the drawing made more sense with the record.

JC:

Yeah. We were just trying out a couple different images, and I think working as somebody that has done album covers for other people and as a designer working on just how to visually communicate stuff, there's also this sense that, with our own stuff, I don't want to do two things: I don't want to micromanage somebody to make a work for the thing, and I also don't want to overly belabor the feeling of the thing. I think they need to either feel like they come together naturally or they shouldn't be forced together. So when we were looking at your work, it's like that same process where you have a record forming—you have music forming—and then you're like, how am I going to present this in a way that people understand the visual connection to it without it being overly literal or maybe a juxtaposition that's not working. We were just placing different things, and we moved into looking at one of your photographs because the title of our record is Different Rooms, and there was a photograph that you had that was a room that had a photograph in it, and a television in it, and that had an image on it. There were just all of these rooms in that room, eventually we were just trying out various pieces of your work to see how it felt. And from there we were just kind of gauging your interest in having your work on the cover. We pivoted to your drawings and tried a couple of those out and then really kind of left it up to you. It was like, "what do you think, Sam?" And you listened to the music and said "this one's a better option."

DB:

So you made the final suggestion / pick, Sam?

SP:

Well, yeah. I mean, they asked what I thought and I said "that one."

JC:

Which I think is important. I think it's tricky. Artwork's always tricky. That's why I'm also curious—you sort of have an approach for all of your solo works, or even The Sea and Cake records, where nowadays they feel pretty cohesive, from one to the next, in terms of just using your photography. I don't know what your thought process is going into that.

SP:

I dream of someone else telling me what to use for a cover. That would be amazing. So I'll be asking you guys next time. I mean, I always feel that it's kind of a cop out on my part to always use my own photos. They're not always my photos. The last Sam and John record, the one with the two cats on the cover [Sons Of, with John McEntire, 2022] I didn't take the photo, but I felt like I took ownership of it by tweaking it just right to take it to the next level. Beyond a casual iPhone photo, which is a good quality of it, but to make it work as a record cover. I felt like I had to throw in some design chops to make it happen. But I love that cover. You can never go wrong with cats on the cover.

DB:

It's pretty effective, honestly. I hadn't seen that cover yet, and then when the record came out, I saw it in a shop and my eyes went right to it.

SP:

Yeah. I think it's probably the reason why most people like that record, is that cover. [all laughing]

DB:

It just opened the door, that's all.

SP:

I'm just laying it out there. Yeah.

DB:

I'm curious how early on ideas of artwork for a cover, or for a package, start creeping into your brains while making a record. I'm sure some people would rather not think about this until they absolutely have to. But for some people it could be something that could even lead them, in terms of finishing a record. What's that look like for the three of you? Marta, I'm also curious about how you interact with visuals considering all of your work in television and film. It seems like there's constantly a visual aspect to everything that all three of you are doing.

MSH:

I mean, that's true, but for most of my work as a studio player, it really is just executing to the picture what other people have scored. We've done a couple scores as a duo where we are composing to picture. So there is an element in that, which to me is enhancing the mood, finding beats within the picture and the music to relate to each other to keep the momentum. But in terms of album art, Jeremiah is such a visual person. He's had a design and art practice for so long, and he is a Virgo [laughing]. We have plenty of conversations about it in terms of our collaborative work, but I do tend to let him take the lead. Like, we'll start with what he's thinking and then we work through it together after that.

JC:

Sam, what do you do? Does it come into the fold early?

SP:

I think for me, I figured out that you can't rely on hoping that something will work until the record's actually done. I almost never do it until the record's complete, so that the music can sort of give you cues as to what way you should go with it. And that's pretty much how it's always been. I think it's a safe way to go. I love designing record covers. I mean, it's a lot of fun just to see what works and what doesn't. It's a super important statement to make along with the music, so it's never just tossed off. It's always a huge decision to make, but I just follow my intuition and if it feels right, it's probably the right way to go. Now, way early on, I feel like we made some big mistakes on album covers.

JC:

Oh yeah? Do tell.

MSH:

Yeah!

DB:

We're not going to get any details on that?

SP:

The first Sea and Cake record—I mean, it's a crazy cover. It's a drawing by a friend of ours. I guess it's potent in its bizarreness, and that still holds up today. I think, formally, it doesn't really work that well, which can be fine. The band just didn't have any sort of visual language yet. That's also a big part of it. Okay. I take it back, it's not bad. It's just sort of undeveloped in a cool way.

JC:

I mean, I think that to me is the whole thing. I feel like I don’t overwork our own covers. It's the same thing with the music. You don't want to hear something and think it's really overdone. You want to leave some level of...it feels like it just hits this point where the considerations were made, but there's still some humanness to it. That it just feels right, and good for what it is. But in terms of when that stuff comes into the process, I think that these days I'm much more thinking about the narrative of the record and the music in relation. And you kind of have a little bit of this imagination about what the tone is and how it reads. So I don't think that I wait until the very end of the music to start to think about the visual portion of it, but only because the timeline is always of the essence. When we're working on stuff it's just like "it's got to get done." So you just have to know that this production timeline is going to overlap the sort of audio production timeline a little bit. And I do think that sometimes it does help finish the thing when you have a couple placeholder images and you can see what it definitely is not. I think that's a really important thing for me, to see what this thing isn't.

DB:

Right. I mean, I would say all of the work that we do at International Anthem is just like, if you look ahead of our schedule, it's just a whole list of things we haven't done yet that we're supposed to have out by a certain time. And it's like, okay, shit, we've got to start doing some of these things now. Does that kind of thing add a significant amount of pressure for you? Do you feel like you're still able to just do your thing, or is it actually beneficial to you?

JC:

I love pressure.

MSH:

We've found deadlines work very well for us. I do think there's a certain, not necessarily pressure, but because the label has gifted us with the fact that its main thing is the medium of vinyl, and then therefore we have a larger dimension for the artwork out there for people to look at and experience. I think that's something that informs the art, because it's going to actually be 12x12 and, like you're saying, you might have that visceral experience in the record shop of noticing something and then checking it out further, versus just a little pixel in the corner of your phone. Which is also another consideration you have to make too, actually.

JC:

That's like the worst consideration, always, but it's the one that you think about all the time now. Like an Instagram feed. Stuff has to read on these damn phones.

SP:

Right, exactly.

JC:

And it's not an ideal surface to cater to. So then, looking at album covers over time, you're basically just going to keep noticing them get simpler and simpler, and the type gets larger and larger.

DB:

Texture kind of goes away too. I mean, there are so many older albums that I have where part of what's so cool about the package itself is that there's these crazy textures on the LP jacket.

JC:

Right, but also what happens now that I've noticed too, is that there's a lot of records that don't have the title on them because most of the time it's sort of wed to a caption or a piece of digital text, where you just have the photograph or the image and then the text is always underneath it anyways on these platforms.

DB:

Yeah, it becomes an issue in physical space, for sure. In record shops, you could look through a whole bin of records where you have to pick up every single one and look at the spine to figure out what it is. Because, unless a label spends a certain amount extra per unit on a hype sticker, it's like, okay, this doesn't say anything. That can be fine and effective artistically, but for the purpose that the record is there in that space it's not effective.

JC:

Exactly. I actually love when that kind of stuff happens in design, where the distribution alters the design.So as an example, like what you're talking about, think about magazine stands. There's a reason that all the titles of magazines are at the very top, because when they sit in stands you can only see that part of it. So the design language of a magazine shifted to accommodate this piece of furniture to showcase the thing. And in some ways, that's also like records. When you're flipping the bins, you're just seeing that top sliver of it. Now you have to pull the whole thing out.

DB:

Sam, I'm curious what sizes you're working with when you're drawing.

SP:

They're like 9x12. So very... [holds up hands] I kind of like art that's, like, the size of your head, you know? [all laughing]

DB:

[hand in front of face] You can just have it right here.

SP:

Well, you can just be here [holding imaginary drawing]. It makes sense, what I'm dealing with. A pencil's this big [holding imaginary pencil]...paper, whatever...and it sort of fills up your head space properly. And same with photos. I don't like huge photos for my own work. I think it also has to do with how books operate. It's sort of that personal space. So the drawings are in that realm. But, for the gestures to go like this [mimes a comically large brush stroke] would be less precise, and not my idea of fun, somehow. So when they're small, you can still be somewhat gestural and the energy, even though it's tiny, can be revealed in a way.

DB:

Would you say that this is all kind of in pursuit of your idea of fun?

SP:

I don't usually say it's fun, exactly. I mean, it's good fun work. I think what I liked most about doing the drawings is that the end of the process just happens over and over, which is nice because you definitely feel like you accomplished something or failed at something every 10 minutes. So it's unlike anything else, and that makes it really different from all my other pursuits.

DB:

How does that compare to when you're painting? I mean, do you work those paintings quite a bit?

SP:

Paintings take much longer. I haven't made a painting in so long. I have a feeling, though, that having figured out how to make drawings like I do now will have an effect on the paintings. My paintings were much more of a mixture of being very deliberate, sort of like the drawings, and in some periods of time it was kind of like busy work.

JC:

Your paintings are on those first two solo records, right?

SP:

Yeah, the first solo album has one of my paintings on the cover. The second one is kind of a digital collage version of one of my paintings.

JC:

And when you're painting, was that scale also 9x12? Those feel a little bigger, no?

SP:

They're not big. The paintings are a bit bigger than the drawings, but not huge. And I usually hold them while I'm doing it. That's kind of like the drawings as well.

DB:

Oh, wow.

SP:

But to finish it, often, I'll have to do something somewhat drastic, where it feels like I've disrupted it enough, but also put a punctuation point on it. Sort of, the final mark. And usually that happens after looking at it and being somewhat disappointed and pushed to frustration to do the one last thing. And that usually finishes it and makes a good. And all these kinds of ideas happen with the drawings. It's just, like, in 10 minutes. And if it doesn't work, whatever, just start another one—which has been the best thing about it. I'm trying to think if there's any music I do that's along those lines— that process of finding new ideas just by messing around in your studio. It's a similar kind of thing. It doesn't have to end up being good. It's the work that's important.

JC:

Right, we're always piecing little chunks of music together as well. These little moments. I always think that that's the most interesting thing about the drawings, and the music, and the photography. It's all just playing with time, and there's these moments of improvising, but we could also just look at an image for all of eternity. Even if it was made in 10 minutes. Or that same thing occurs in music ,where it's a snapshot of a thing, but you can just infinitely experience it. And that sort of malleability, with just thinking about these time formats. Whether it's a still image or a piece of music, I think it's fun.

DB:

Yeah, totally. And all of those processes tend to inform one another in some way. Like Sam, talking about how eventually when you dive back into painting one day, it's no doubt going to be influenced by the way that you're drawing now.

SP:

Yeah, totally. I mean, people often ask me, how does the art relate to the music? And my basic answer is, well, I did both of 'em. Yeah, I do both. There's no way around it.

DB:

Have you always done both? Did you draw a lot as a child?

SP:

I did actually, yeah. The music thing came later. It happened while I was in art school. But I kept making art, obviously, while I was doing it. One distinction with the music is it's often with other people, and that's a whole other layer that I miss lately, somewhat, where you have to deal with what other people are doing as well. And that can be super helpful. It's kind of like Jeremiah and Marta asking what I thought about whether it should be a photo or drawing on their record. It's good to have other input. I've been sort of doing more remixes lately, which I really like doing, and which is sort of like working in a band, because I feel like they need to be into it as well. I need to feel like I did my best work, but it has to fulfill their needs and goals with it as well, which is nice. I don't have to decide everything, basically. Some raw material from them is useful.

DB:

When you're doing a remix, how much of a prompt do you tend to get from somebody? Or is it pretty much just a free for all?

SP:

Usually if somebody's asking me kind of know...I sort of do recombinations of things. I sort of end up making my own track with their material. So I'm not really a remixer, exactly. Basically they're like "here's my tune, do whatever." And they have to say, "do whatever you want", otherwise that's not going to work.

DB:

Yeah, totally.

SP:

I always tell them that I only know how to do what I know how to do. When people ask to play with me I'm like, we could try that but it would have to be my way or the highway because I'm not terribly adaptable to other ways of working. [laughing]

JC:

That's how you send your response? Like "my way or the highway"?

SP:

[laughing] yeah, and they're like "sounds good."

JC:

That all tracks. I mean, remixes are interesting things because they are a little like "does somebody have an idea?" I mean, they always have an idea, right? But they don't always tell you what that's going to be. And then you're sort of left to your own devices. You want to make something that's good, but it's mostly just doing your process, doing your thing.

SP:

Yeah. That's what most people want. They just want you to do something with it.

DB:

Totally. But then it's like the invitation itself is based on their perception of what you do. So hopefully it's like what you're actually going to do.

SP:

Right.

[after this, the casual conversation became more casual, taking a turn toward Sam and Marta’s coffee setups, promises to come visit, etc.]

Follow the artists:

Bandcamp: samprekop.bandcamp.com

IG: @1sampre and @prekopcomma

Tracing The Lines is a creative exploration of International Anthem Recording Co. and the community that surrounds it.

Order print copies